Multidimensional poverty is experiencing a lack of many basic essentials that we take for granted. Understanding it is therefore about exploring the facets of deprivation.

Deprivation

The most common factor indicating poverty has traditionally been the lack of money. Today, the international poverty line is $2.15 per person per day – that’s less than $800 dollars a year. In 2019, some 701 million people around the world lived on less than that.[1] With that in mind, you might be surprised to know that nearly half the people who experience poverty around the world are not necessarily money-deprived.

A deprivation is a lack. When you consider being poor, can you imagine all of the things – necessities as well as luxuries – of which you would be deprived? Multidimensional poverty considers those deprivations that impact quality of life, or well-being. This more nuanced understanding of poverty not only helps us to understand how living in poverty impacts individual lives, it also brings to light how earning more than $2.15 a day doesn’t automatically raise a person out of poverty. In fact, according to World Bank, nearly 4 out of 10 multidimensionally poor individuals are only deprived in nonmonetary poverty dimensions.[2] Common factors include the availability of clean water and sanitation, the ability to obtain an education, access to health services, and having safe and adequate shelter. These features are often linked, and deprivations often go hand-in-hand for generations. By considering each factor, we begin to unravel the causes of systemic, multi-generational poverty around the world.

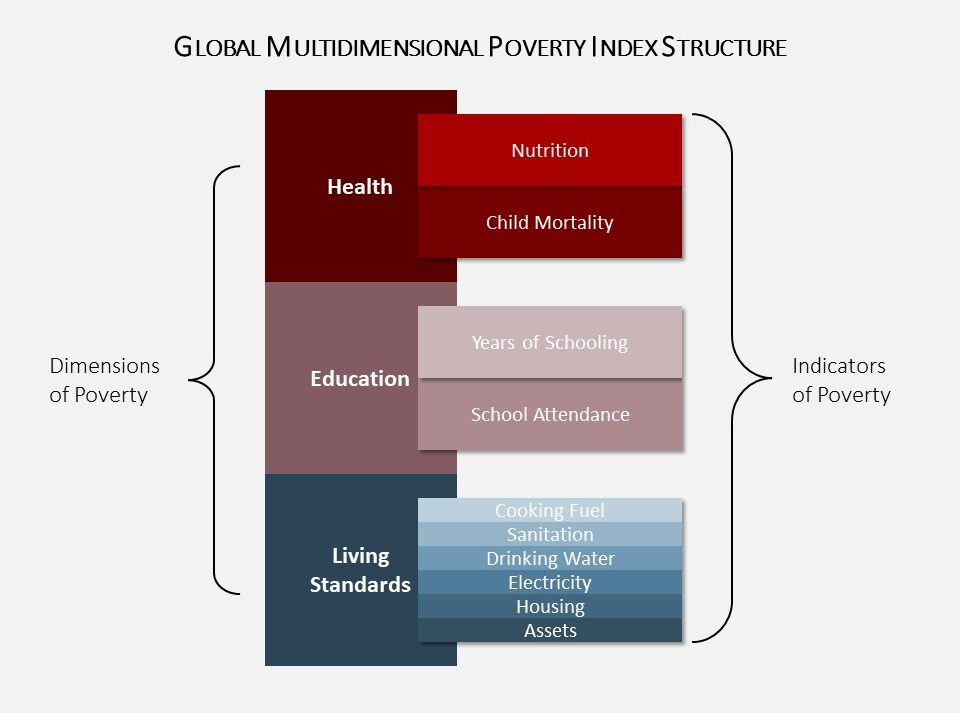

There are various methods for measuring multidimensional poverty, for example the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), developed by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), pictured right. As a framework for measuring deprivations, each characteristic holds a certain weight that, when added together, reveal the degree of multidimensional endured. There are many questions to investigate when using this index, such as whether children are currently enrolled and attending school or adults ever received a basic education, whether there is an improved source of water within a 30-minute walk, or whether there are private bathrooms or if sanitation facilities are shared by entire communities or not present at all. The resulting number after evaluation is called a deprivation score, and must be less than 33.3% for an individual to be considered not poor. More than 1 billion people worldwide are multidimensionally poor, and some 5 of 6 of them live in either Sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia. In fact, more than half the population of Sub-Saharan Africa is multidimensionally poor. In The Gambia, for example, 18% of the population experiences multidimensional poverty; in Ghana 33%, and an astonishing 80% in Niger.

Want to Know More?

Check out this World Bank article with Interactive Map!

Focus

As we begin to pick apart the nuances of poverty, it is possible to focus on specific groups, such as women and girls, to determine their degree of deprivation within their communities. One such group only recently gaining attention is children. Recent studies by the World Bank and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNIECF) indicate that children are disproportionately likely to live in extreme or multidimensional poverty. In fact, they are more than twice as likely to endure these hardships than adults – one in three children around the world are multidimensionally poor. Studying multidimensional child poverty has to be nuanced. The key is measuring current deprivation impacting a child’s well-being rather than anticipating tomorrow’s, because differing ages have differing needs when it comes to well-being. When evaluating an infant of only 4 months, for example, in comparison to a teenager of 14 years, a lack of educational opportunity is going to be far more relevant to the 14-year-old than to the baby.

Infrastructure

Virtually every country is home to individuals experiencing poverty or multidimensional poverty. High-income nations, on the whole, have fewer. One reason for this is the basic fact of underlying infrastructure. These countries are going far fewer people living in areas where there is a lack of clean water or sanitation, for example, because water treatment facilities and adequate sewers are a basic fact of life for most. Lower-income nations that do not have the benefits of established infrastructure, on the other hand, have greater numbers of individuals who suffer. Poor sanitation, struggling public health sectors, and a lack of clean drinking water makes achieving good health and longevity a challenge even when an individual earns more than $2.15 a day.

As we continue to explore the many facets of experiencing poverty, the information gathered is invaluable to policy-makers. It offers a glimpse into the heart of a nebulous problem and allows policy-makers to enact changes that will have greater impact. Perhaps everyone in the world cannot become rich overnight, but by focusing on improving infrastructure so more people live with decent sanitation and schools are built strategically so more overlooked children have the ability to receive an education, we can uplift future generations and build a world of good well-being for all.

Further Resources:

https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2023-07/2023mpireportenpdf.pdf

[1] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/measuringpoverty

[2] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/brief/multidimensional-poverty-measure